Spotting Alzheimer’s Early Could Save America $7.9 Trillion

A new report says the cost of care will increase by $20 billion in just one year. While there’s no cure, quicker diagnosis might lower the price tag

Alzheimer’s disease is among the most expensive illnesses in the U.S. There’s no cure, no effective treatment and no easy fix for the skyrocketing financial cost of caring for an aging population.

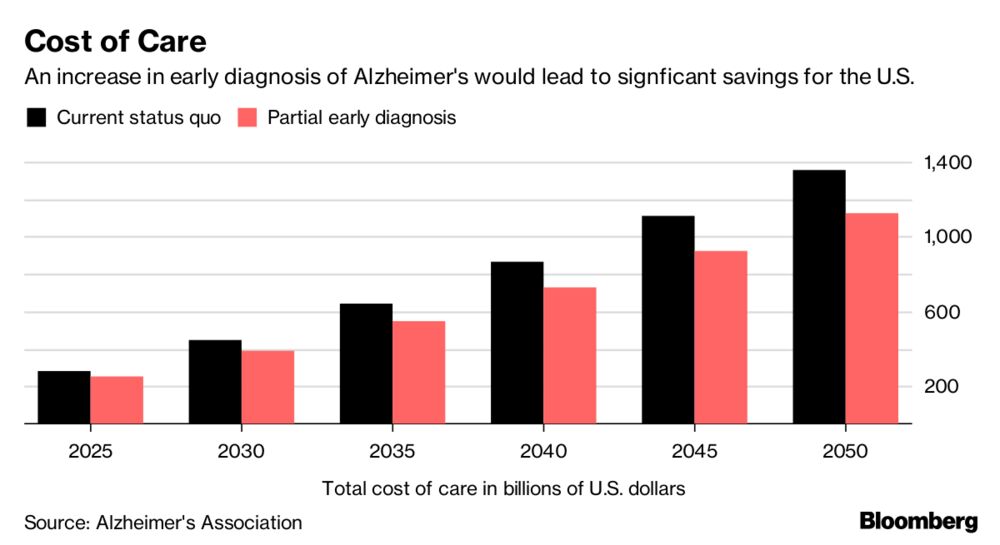

Spending on care for people alive in the U.S. right now who will develop the affliction is projected to cost $47 trillion over the course of their lives, a report issued Tuesday by the Alzheimer’s Association found. The U.S. is projected to spend $277 billion on Alzheimer’s or other dementia care in 2018 alone, with an aging cohort of baby boomers pushing that number to $1.1 trillion by 2050.

Research so far has been stymied by clinical failures. By one count, at least 190 human trials of Alzheimer’s drugs have ended in failure. No company has successfully marketed a drug to treat it, though many big pharmaceutical companies, including Merck & Co. and Pfizer Inc., have tried. Biogen Inc., a company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, saw its shares dive last month after it said it was expanding the number of participants in its trial for the drug aducanumab.

However, significant cost savings can be achieved, according to the new report, by the simple act of early diagnosis. Currently, individuals are typically diagnosed in the dementia stage, rather than when they have developed only mild cognitive impairment [MCI]. Identifying the disease early can allow it to be better managed, in part with existing drugs that treat its symptoms. In doing so, the study postulates, America could save $7.9 trillion over the lifetimes of everyone alive right now.

The Alzheimer’s Association commissioned researchers at Precision Health Economics to study the potential savings of obtaining an earlier diagnosis. It used data from the Health and Retirement Study, a “nationally representative sample of adults age 50 and older” run by the University of Michigan and supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration.

The $7.9 trillion in savings was derived from a scenario in which all adults who develop Alzheimer’s receive an early diagnosis in the MCI stage. The cumulative cost in such a circumstance is projected at $39.2 trillion—far below the $47.1 trillion that would be spent under current diagnostic patterns.

“We know that there’s a spike in medical spending around the time of diagnosis,” said Keith Fargo, director of scientific programs and outreach for the Alzheimer’s Association. “It’s actually quite expensive to do things that way.”

“You can save a significant amount of money just through better early diagnosis,” he said.

“You can save a significant amount of money just through better early diagnosis,” he said.

For example, managed dementia is less expensive to treat because it reduces the chances of missing medication or incurring avoidable costs, Fargo said. It’s more costly to be diagnosed in the later stages because that’s likely to occur only after an expensive trip to the hospital.

The cost of caring for Americans with Alzheimer’s will rise by $20 billion this year, compared with 2017 spending. That doesn’t include the burden that falls on unpaid caregivers such as family and friends, who last year provided 18.4 billion hours of unpaid care—which the report estimated to be the financial equivalent of $232.1 billion. The hours were calculated based on a follow-up analysis of results from the 2009 National Alliance for Caregiving/AARP national telephone survey, multiplied by an an average of the federal minimum wage and the mean hourly wage of home health aides.

Even worse is the reality that the disease’s prevalence will rise over the coming decades. There are now an estimated 5.5 million Americans aged 65 or older with Alzheimer’s. In 2025, that number is projected to be 7.1 million. By 2050, it could reach 13.8 million.

Along with the increasing costs, the report also found Alzheimer’s to be increasingly lethal. It’s currently the sixth-leading cause of death in the U.S., and deaths attributed to it jumped by 123 percent from 2000 to 2015, the report found. During the period, the number of deaths from heart disease—the top killer among Americans—decreased by 11 percent, the Alzheimer’s Association said.

While early diagnosis is a good first step, Fargo emphasized that scientific research is the only way to solve this growing health crisis. “I really think that’s a key call to action,” he said.

The Billionaire Whisperer Who United Bezos, Buffett and Dimon

Todd Combs was crucial in getting their health-care deal off the ground. Up next: Find a CEO to run the venture.

Todd Combs spends most of his days reading in he’s an investment manager at Berkshire Hathaway Inc. But one day last year he found himself on a flight to Seattle with an unusual mission: Pitch Jeff Bezos on a bold idea for wringing costs out of the U.S. health-care system.

Two of the biggest corporate chieftains in America—his boss, Warren Buffett, and Jamie Dimon, who runs the largest bank in the country—had already signed on. But they wanted the Amazon.com Inc. chief executive officer on board as well.

Combs, 47, a former hedge fund manager who has no experience in the health-care industry and likes to keep a low profile, was both an odd and an obvious choice as the CEOs’ emissary. He had won Buffett’s confidence at Berkshire, where he sparked the company’s largest acquisition, and he’d impressed Dimon so much when the banker visited Omaha that he was invited to join the board of JPMorgan Chase & Co. in 2016.

The outreach to Bezos worked. In late January the three billionaires announced they were teaming up to form a company, free from “profit-making incentives,” that would seek to lower the cost of covering their hundreds of thousands of employees. Details were scarce, but health-care stocks promptly plunged. Some of the smartest minds in business were about to try fixing a notoriously wasteful industry—one that costs America some $3.3 trillion annually.

For Bezos, Dimon, and Buffett, it was another splashy headline in careers that have pushed boundaries. Behind the scenes, though, Combs largely spearheaded the effort, according to a person familiar with the matter. For months, Combs shuttled among the CEOs to get them to commit to doing something about a problem they’d discussed informally for years, the person says.

This was probably just how Combs wanted it: involved in the action but out of the spotlight. The Florida State University graduate was a virtual unknown in investing circles when Buffett hired him in 2010 to manage a portion of Berkshire’s vast stock portfolio. At the time, one of the few photos that news outlets could find of him was a boyish high school yearbook shot. Since then the world hasn’t gotten to know Combs much better. (He declined to be interviewed for this story.)

This much is clear: Over the past seven years, Combs has become an influential figure at Buffett’s conglomerate. In addition to investing a slug of Berkshire’s money, he was behind the $37 billion purchase of Precision Castparts Corp., a supplier to the global aerospace industry, and worked on well-publicized trades that saved hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes.

Combs is already in line to manage a huge swath of Berkshire’s investments when Buffett, 87, leaves the scene. But his ever-growing portfolio has led some shareholders and analysts to speculate that he could one day become CEO as well. “Everybody else is a slave to attention, and Todd seems indifferent to it,” says Steve Wallman, a longtime Berkshire investor and money manager in Wisconsin, who’s met Combs. “This is just the kind of behavior you want to see in someone who’s lined up to succeed Warren.”

Combs is also a talented networker who has used his smarts and drive to win the confidence of powerful men, according to interviews with a dozen people who know him. Most asked that their name not be used, even when they had positive things to say, for fear of jeopardizing their relationship with someone who values his privacy. Many of these people say they were surprised to learn about his involvement in the health-care initiative, given his lack of background in the industry.

What Combs does know is financial services. A native of Sarasota, Fla., he graduated from college in 1993 and took a job with the state’s banking regulator. From there he went on to Progressive Corp., working in a group that studied risk and determined what to charge for auto policies.

In 2000, Combs started his MBA at Columbia Business School. It was a chance to learn securities analysis in the same halls where Buffett had long ago learned the craft from Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing.

His first encounter with Buffett came during a talk that year. The Berkshire CEO told students that one thing they could do to get ahead was to read 500 pages a week, Combs recalled in a 2014 interview with CNBC. The billionaire’s point, he said, was that an investor could compound knowledge and get better over time.

Richard Hanley, a hedge fund manager in New York, was an adjunct professor in the MBA program back then. Combs, he says, had a deep drive to get ahead and the mental flexibility to come up with smart ideas. One assignment Hanley gave his students was to devise a trade that would have the best performance over the next several months. Unlike his peers, Combs decided to short the stock he picked. Hanley forgets the company Combs bet against, but his idea beat everyone else’s. “Todd was very intense, very focused,” Hanley says.

Buffett’s advice about reading stuck with Combs as he started his investment career, first as a financial-services analyst at Copper Arch Capital and later at Castle Point Capital Management, the hedge fund in Greenwich, Conn., he started in 2005. Combs’s approach was a race against the clock to consume information, says one person familiar with his strategy during that period. At Castle Point he’d get to the office early and leave late. If he wasn’t in a meeting with his analysts or taking a break to exercise, he was reading, three people say.

He was fascinated by psychology and the sorts of biases that drive decision-making. Books such as Talent Is Overrated and The Checklist Manifesto have become staples in the hedge fund world, where money managers are constantly looking for an edge. But Combs was interested in those ideas well before they became trendy, one person says. Every month or so, he’d pick a book and get together with his analysts to discuss it.

In early 2007, Buffett said in his annual letter to Berkshire shareholders that he was looking to hire at least one younger money manager who would be able to succeed him as the company’s chief investment officer. Résumés poured in, and Combs threw his own into the mix. But it didn’t stand out.

Castle Point’s mandate was to invest in financial-services stocks. His company had done well but not exceptionally so. It was also relatively small, overseeing about $400 million. Combs’s big accomplishment was navigating the 2008 financial crisis relatively unscathed. His fund ended down 5.7 percent that year, while the S&P 500 plunged 37 percent, according to a letter to investors.

In 2010, Combs asked Buffett’s longtime business partner, Berkshire Vice Chairman Charles Munger, for a meeting. Soon after, the two met for lunch at the California Club in Los Angeles and ended up having a conversation that stretched for hours, according to an article at the time in the Wall Street Journal. Afterward, Munger suggested to Buffett that he meet the young money manager. Beyond his apparent smarts, Combs had the sort of personality that was a “100 percent fit” for Berkshire’s culture, Buffett told the newspaper. Mark Nelson, chairman of investment manager Caledonia in Sydney, who had encouraged Combs to reach out to Munger, says he was surprised by how quickly Berkshire acted. Combs enjoys digging into complex financial companies and tearing apart the accounting, Nelson says. “They probably saw a kindred spirit.”

Combs joined Berkshire early in 2011 and eventually moved his family to Omaha from Connecticut. Ted Weschler, the other investment manager Buffett hired to pick stocks at Berkshire, chose to stay in Charlottesville, Va. People familiar with the two men’s arrangements say Combs’s decision to relocate means Buffett leans on him more. In public, however, the billionaire has tried to treat both equally, saying that Combs and Weschler have been great additions to the company and have “Berkshire blood in their veins.”

Sitting next to Buffett has had other benefits for Combs, who now manages about $12 billion for Berkshire. Dimon was introduced to Combs by the Omaha billionaire, which led to the young investment manager joining the JPMorgan board.

In some respects, Combs’s life hasn’t changed much from his days running a hedge fund. “I read about 12 hours a day,” he told the Florida State alumni magazine last year in a rare interview. “Warren and I will usually catch up once or twice a day on stuff that’s going on—deals, stocks, stuff with our companies. Sometimes our managers reach out or a banker calls with an idea, but that’s about it.”

There’s also travel for board meetings. In addition to JPMorgan, Combs is a director of a few Berkshire subsidiaries, including Precision Castparts and Duracell, the battery maker Berkshire purchased from Procter & Gamble Co. in a tax-saving stock swap Combs negotiated.

Less well-known is the time Combs spends hobnobbing with people at the top of the business world. In January he was with Buffett at a Washington luncheon hosted by Vernon Jordan, the Democratic power broker, before the annual Alfalfa Club dinner, a black-tie event where billionaires and politicians mingle. U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross and Dimon were also there, according to a person who attended.

If Combs has settled on an approach for the new health-care venture, he’s remained tight-lipped about it. People who know him speculate that the company could initially focus on squeezing costs from middlemen who take a cut of prescription drug sales. But the ambitions are clearly wider. “It would be very easy, I think, to go in and shave off 3 or 4 percent just by negotiating power,” Buffett said on CNBC in late February. “We’re looking for something much bigger than that.”

The U.S. health system has powerful incumbents, including hospitals and drug-benefit managers. Years of efforts to curb costs haven’t accomplished much. Bezos, Buffett, and Dimon have united around a common cause, but their plan could run aground if the needs of their wildly different businesses aren’t met.

For now, the focus of the group is to find a CEO to run the new venture, a process that Combs is working on with deputies at JPMorgan and Amazon. One person says Combs may end up being the health-care company’s nonexecutive chairman, given how much work he’s put in so far. Were that to pass, it would be a way for him to stay involved—but remain comfortably in the background. —With Hugh Son and Spencer Soper

Comments

Post a Comment